When people hear about “spoken chess”, they often look puzzled. In their minds, chess is a game of silence —two players, eyes fixed on the board, calculating in solitude. In tournaments, silence is sacred: no comments, no hints, no dialogue.

That’s why, when we tell teachers that in our classrooms children play chess in pairs, aloud, and together, they usually raise an eyebrow. But then they smile. Because it makes sense.

Behind this small change —allowing students to talk— lies a powerful educational shift.

From silence to shared thinking

Educational chess is not about reproducing competition. It’s about building spaces where thinking becomes collective.

When two children discuss whether to move the Queen or the Bishop, they are not only playing a game —they are reasoning, explaining, negotiating, listening. They are thinking together. Talking while playing makes thought visible. It transforms an abstract mental process into dialogue, argument, and collaboration.

This is the heart of the TRACIS methodology, which we’ve developed in partnership with universities and schools: turning chess into a tool to learn how to think, not just how to move.

One hour that changes everything

Many schools dedicate only one hour a week to chess within the regular timetable. Yet that single hour can transform the classroom climate. It’s not “one more subject”. It’s an hour of cognitive and emotional training.

During that time, students learn to slow down before acting, to observe calmly, to justify their ideas, and to listen to others. When a child says, “Your idea is better —let’s try yours,” they are not just being polite. They’re developing critical thinking, empathy, and mental flexibility.

And when a teacher asks, “What would happen if you made that move?” instead of correcting, they are teaching reflection —the skill that underpins all deep learning.

Making thinking visible

In traditional chess, thought is invisible. In educational chess, we make it audible. We want to hear the reasoning, the doubts, the discoveries. When students explain out loud why they choose a move, they connect action with reflection. When they listen to another perspective, they train flexibility and tolerance.

Over time, the classroom becomes a laboratory of thinking: errors become hypotheses, and silence gives way to dialogue.

Beyond the board: reading, reasoning, and living together

Chess trains more than logic. It also improves reading comprehension, problem-solving, and social coexistence.

To “read” a position, one must interpret, anticipate, and evaluate relevance —the same skills required for reading a text or solving a word problem. To play cooperatively, one must take turns, accept mistakes, and respect others’ ideas.

Thus, chess is not an isolated subject: it’s a bridge between cognitive and emotional learning.

Inclusion through the board

The chessboard is an equalizer. Every child starts from the same position, with the same opportunities to think and create.

Students with learning difficulties often thrive here because chess is visual, structured, and tangible.

Meanwhile, because educational chess offers differentiation options, high-achieving students can go deeper, explore strategies, or even teach peers. Educational chess doesn’t separate —it includes.

The teacher as guide, not referee

In this approach, the teacher’s role changes profoundly. They are no longer a referee or instructor, but a thought guide —someone who provokes curiosity and supports reflection. Their goal is not to produce tournament players, but independent thinkers.

A teacher who listens to a child’s reasoning, even when it’s wrong, and asks, “What made you think that?”, is cultivating metacognition —the ability to think about one’s own thinking. And that is the foundation of lifelong learning.

Thinking, speaking, transforming

Over the years, I’ve witnessed how chess changes students’ ways of thinking. I’ve seen quiet children find their voice explaining a move. I’ve seen classes where competition turned into cooperation, where listening became natural, and where reflection replaced impulsivity. That’s why in our classrooms, playing without talking is forbidden. We want thinking to be heard, shared, and co-constructed.

Educational chess doesn’t train champions —it trains thinkers. And when children learn to think with others, schools begin to change. We see this as part of a global movement to make thinking visible, learning collective, and education more human.

About the Author

Ramón Pérez Rodríguez, Degree in Primary Education from the University of Girona and in Psychopedagogy from the Open University of Catalonia. Coordinator and teacher of the Educational Chess Program during school hours “EduEscacs” and the Teaching and Learning Method of Educational and Social Chess “TRACIS” applied to FEDAC Schools in Catalonia. Educational chess trainer for teachers and professors of the Department of Education of the Generalitat de Catalunya from the School Chess Project. Member of the Chess and Educational Research Observatory of the University of Girona. Website coordinator: eduescacs.cat

Ramón Pérez Rodríguez, Degree in Primary Education from the University of Girona and in Psychopedagogy from the Open University of Catalonia. Coordinator and teacher of the Educational Chess Program during school hours “EduEscacs” and the Teaching and Learning Method of Educational and Social Chess “TRACIS” applied to FEDAC Schools in Catalonia. Educational chess trainer for teachers and professors of the Department of Education of the Generalitat de Catalunya from the School Chess Project. Member of the Chess and Educational Research Observatory of the University of Girona. Website coordinator: eduescacs.cat

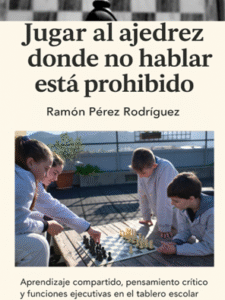

He is the author of the book shown on the left with a picture of students from the FEDAC Schools of Catalonia. The book is expected to be published in Spanish in December or January. [English title translation: Playing chess where talking is not prohibited]